External Sex Characteristics and Gender

August 09, 2020

Note: This is the third post in a series interrogating the claim that gender is best understood as a binary phenomenon. The first two are Chromosomes and Gender and Reproduction and Gender.

At the beginning of this series, we observed some of the key claims of Complementarianism, along with the assertion of one of its major proponents that the whole system falls apart without a stable, binary model of sex and gender.

We’ve been exploring the feasibility of creating such a model while remaining grounded in our current understanding of biology. In the earlier posts, we evaluated chromosomes and gonads, and found that they have too much ambiguity for the purposes of a system like complementarianism.

In this post, we’ll turn our attention to the more easily observable sex characteristics. There are several potential advantages to using these features as the basis for a model of sex and gender:

- They would have been available to the original audiences of the Bible.

- Modern doctors typically use them to assign sex at birth.

- They’re what we most commonly use to guess the gender of an individual in casual interactions.

We’ll begin our analysis with the way that sex is typically assigned at birth: someone takes the newborn, observes the genitals, then declares, “It’s a girl!” or “It’s a boy!”

…At least, that’s what usually happens. However, in some cases, this method does not yield a clear result. For example, children with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia or Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome may be born with ambiguous genitalia, as described by the Prader and Quigley Scales. While we tend to think of genitals as being one of our most binary features, the reality is that they also exist on a spectrum without a clear dividing line between male and female.

To make things even more confusing, a condition called 5α-Reductase deficiency sometimes results in a genital configuration that appears feminine at birth (causing an assignment of female at birth) but masculinizes at puberty. While some children embrace this transition and experience a sense of relief when they are able to live as boys, others find the changes unwelcome and choose to remain in the female gender role.

Clearly, genitals are not sufficiently unambiguous—let alone stable—to serve as the basis for a binary model of sex.

Along with the other posts in this series, we’ve now covered all of the major, known sex characteristics that can be examined at birth. This is a critical point, as complementarians often prescribe different parenting strategies depending on the gender of a child1. If we cannot accurately assess the sex of our children from birth, then much of this advice must be discarded as impracticable.

However, let’s assume for the moment that there are aspects of complementarianism that can be salvaged as long as we can unambiguously determine the sex of adults. This gives us a number of additional options to consider, as there are quite a few characteristics that only become apparent at or after puberty. Here are a few:

- Facial / body hair

- Breast size

- Susceptibility to baldness

- Laryngeal prominence (Adam’s apple)

- Shoulder-to-waist ratio

- Waist-to-hip ratio

- Elbow carrying angle (yes, really!)

- Height2

These traits are frequently described as “secondary sex characteristics”, and they’re the first characteristics that we’ve discussed in the series that actually impact how we typically assess (consciously or subconsciously) the sex of another person during everyday interactions.

However, with the possible exception of the elbow angle3, all of these features are also heavily influenced by environmental factors. (or hormone levels, which themselves can be strongly affected by other environmental factors) This makes it difficult to argue that any of them represent the essence of masculinity or femininity.

To take just a couple of examples:

Breast development is typically considered a “female” trait. However, children assigned male at birth can develop gynecomastia at puberty, which causes significant development of breast tissue—which may or may not subside as they grow older.

Similarly, a laryngeal prominence is considered a “male” trait, but its development is a response to a certain level of testosterone in the body, making it possible for anyone to acquire one. (unlike gynecomastia, once it develops, it’s there to stay unless surgically altered)

At this point, one might begin to wonder—with all of these exceptions—how we even manage to maintain categories like “man” and “woman”. When you meet strangers—who tend to be fully clothed and whose medical charts you have not perused—you often make a snap decision on whether to call them “he” or “she”, and more often than not, your choice matches the choice they would make for themselves. How do we reconcile all of the ambiguities we’ve found with the apparent ease with which we consistently assess the sex of strangers?

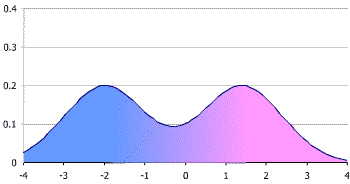

The answer to this conundrum comes when we discard our binary theory of biological sex in favor for one that is bimodal.

In a bimodal distribution, values tend to cluster at around a couple of points, but they can also appear at far extremes or at points that are difficult to classify.

The concept of a bimodal distribution provides a much better tool for explaining what we’ve seen up to this point:

Most people have either XX or XY chromosomes. Most men have testes and a penis, and they produce sperm. Most women have ovaries, a uterus, and a vagina, and they produce eggs and can carry a fetus to term. Most men have high levels of testosterone, while most women have high levels of estrogen. Most people have bodies that can properly process testosterone and estrogen. On average, men tend to be taller and stronger than women. Most people cluster sufficiently closely to our notions of “male” and “female” that they are easily identifiable as such.

This provides an explanation for the consistency with which we choose “male” and “female” labels for each other while also leaving room for all of the variation that we’ve seen in this series. However, it does not leave much room for systems of thought that require all people to be assigned to one of two categories.

One might respond to this realization with the proposal, “Let’s just choose an arbitrary point on the spectrum as the divider between ‘male’ and ‘female’.” While this could produce a binary system, the arbitrariness of the choice would undermine any claims of “Biblical authority” for the Complementarian position: since the Biblical writers never addressed these concerns in detail, there’s no reason to believe that our choice would match up with the original intent. (in fact, basing one’s choice on a feature like chromosomes guarantees that our model of gender will not match Biblical models)

However, we haven’t yet explored all of the categories that we laid out at the beginning of the series:

ChromosomesSecondary sex characteristicsHormone levelsGonads (internal reproductive organs)Genital configuration- Gender identity (at least insofar as it has been linked to brain structures)

Is it possible that we’ll find the basis for a binary theory of gender in the last place most Complementarians would want to look? At this point, it seems unlikely, but we’ll have to wait until the next post to get into it.

- As a case in point, consider this post, written by the Executive Director of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, in which he expresses his dismay that Target removed its “boy” and “girl” designations from toy aisles.↩

- I admit that I deliberately chose this example for its absurdity. However, it is considered a secondary sex characteristic!↩

- I have not researched what causes differences in elbow carrying angles.↩